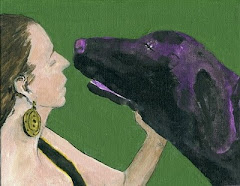

Tosca was my blond bitch, lighter on her feet than the color of her fur. I rescued her one winter night, shivering at the feet of two gypsy men sharing a cigarette outside a circus in Jerusalem. The circus performance, which a friend and I had attended, had been a seedy affair, the acrobats and performers as ragged and dusty as their faltering tent. Depressed by the show and the grim winter night’s cold, we were heading toward the bus stop when we heard the men falling into a loud argument. We turned to see them landing a beating on the dog with each rant.

“Hey!” I screamed, stopping in my own tracks. “Don’t do that to

the dog!”

The men gawked at me, uncomprehending neither my English nor

reason for fury. In their world a dog was no better than a rat, and they would

just as soon have lit the animal’s tail on fire as ignite their cigarettes. I

ran toward the convulsing creature, grabbed her up into my arms, and lurched

off in search of a cab. The ride home cost nearly my entire week’s salary.

This occurred in the fall of 1971, after my return to Israel

following a life three years earlier on Kibbutz Tzorah, where I’d experienced

that agricultural outpost as a spiritual playground. Kibbutz life had

reawakened a tomboy self long lost in the girl who’d arrived a shy academic.

I’d spent my days there in mud-kicking work boots and shorts, pruning trees in

the peach, plum, and persimmon orchards, breakfasting on Turkish coffee and

blood oranges, and flirting like a sun-baked version of my childhood hero,

Sheena, Queen of the Jungle. Aside from the constant murmur of complaining and

joking, the only sound that disturbed the quiet of that desert orchard was the

brief, of a tinny-bright train whistle

at the orchard’s perimeter. The train could have been no longer than five cars,

for, by the time the sound of the whistle had sailed off into the sky, the

tracks were empty. Every day I wondered where the train went and who was riding

on it.

In comparison with the air of hope in Israel following its

victory in the ’67 war, the despairing political climate of the U.S. made

infused me with an unfamiliar optimism. For while I was happily moving

irrigation pipes, the U.S. was exploding: Robert Kennedy and Medger Evers,

assassinated; Washington in flames; riots and bomb threats; anti-Viet Nam

protests; students shot dead at Kent State university. I saw no reason to

return.

But, reluctantly, I had to finish college. This new life in

Jerusalem was my return – I found a job as an international correspondent at

the Israel Museum and an unusually spacious apartment. The six-day work week in

an orchard and a six-day work week in an office, even if it was in a museum

with a sculpture garden designed by Isamu Noguchi and exquisite collections of

Ashanti gold figures. Even if. Even oif. Even if… With November came chilling

rain. The spacious rooms with their twelve-foot ceilings and stone floors –

perfect for keeping out desert heat, but the familiar, but unidentified effects

of clinical depression. my spirits as gray as the dulling skies. Thus, when a

friend suggested we spend an evening at the circus, I jumped at the invitation.

Jerusalem sits on a hilltop, and its winters then were cold

enough for snow. The only heater -- a small kerosene stove -- radiated a circle

of warmth no wider than four feet. Even curled up in bed with the dog, whom I’d

named Tosca, I could never get warm. Some nights I awakened to find snowflakes

drifting around my head. On those occasions, Tosca would have worked open the

French doors to stand outside on the terrace listening, looking, sniffing in

the muted night.

My new blond girl took to her new surroundings with an

alacrity that far surpassed my own adjustment to transplantation. She bounded

with happiness on our walks, her ears perked, her tail high. Tosca seemed to

grow healthier by the day, and within a week or two, her scrawny silhouette

grew round. I congratulated myself on my nurturing. Then it became evident that

Tosca was pregnant.

Until the last days of her pregnancy, she was ready at any

moment for play. Then her eyelids began to hang as heavy as her laden teats,

giving her a look of savage sadness. She walked with the tentative step of a

recovering invalid, each paw meeting the floor with deliberation. Then, the

pups were sprung from her womb. Within days her step was reignited, and once

again she was ready to fly.

With the promise of spring in the air and Tosca liberated

from her pups, which had found homes through a vet, I decided to take us both

on an outing -- a visit to Tzorah. My spirits would be refreshed, and Tosca

could run unleashed and exultant. It was Sabbath, of course, the country’s one

day of rest. We drove with a friend from Tzorah, also now living in Jerusalem,

and my heart did, in fact, soar at the vision of the familiar vineyards and

trees and campus. Tosca was practically eating the air in excitement. We

strolled toward my old quarters and down familiar allees. I recognized friends from the orchard.

Passing one of them on the path, I anticipated the offering of a fond hello.

Instead, he gestured at Tosca and spat toward me a few unpleasant words in

Hebrew. Turning back toward the dining hall, I was again greeted with hostile

glances or remarks. Finally, I realized that, never actually seen a dog on the

kibbutz during all the time I’d lived there, perhaps they weren’t so

welcome. I’d assumed Tosca would be

looked upon with the same affection as dogs in America, but discovered instead

a prevailing pioneer attitude: “We work too hard surviving to be wasting attention

on animals.” I led Tosca toward the car, wishing that this time she could

scoop me into her

arms to run away.

Summer approached. Tosca, playful and grown beautiful,

flourished; I, on the other hand, was steadily diminishing. By fall, I realized

I simply couldn’t face another punishing winter or more cultural

disappointments. The weight of transplantation had became too much for my

emotionally skeletal constitution. But to consider leaving Israel was to

contemplate abandoning Tosca. I would have to find her a new home.

I placed a classified ad in the Jerusalem Post, and a

family living outside of Haifa responded. They had a small farm, they told me,

and Tosca would have plenty of land across which to run. I was advised to bring

her to Haifa by train where they would meet me.

I was a wreck. I was leaving my dog. I was leaving Israel,

again. I was back to wandering.

The only requirement for the train trip was that Tosca wear

a muzzle. I packed her favorite toys and the chewed up sweater she like to

sleep with. She was allowed to sit with me. She was calmer than I was. In fact,

she looked out the window as if truly curious about where we were going. Half

an hour out of Jerusalem, I began to notice familiar terrain. Date palms,

artichoke fields. Then orchards. Peach, plum, persimmon. The train whistle

blew. I knew where we were and who we were. Who were the people on the train and

who, I then wondered, might be listening for us from the orchards.